Long Eared Meditations

Thom Haxo

“If you can do so much with reality, what can it do if it could fake out what’s not real, or what it is, as opposed to what it’s trying to be?”

Interview by L. Valena

First, can you describe what you responded to?

It was a video. I refused to look at it at first, because I felt like I had to get myself together first. Then half a day later or so I looked at it- it was this little short video of a cloth moving in and out. I responded to the folding, the linework. The covering, revealing. The repetition- the infinite nature of the looping video. The way the drawing was made from a small line to a larger line.

Where did you go from there?

Usually, in any type of collaboration, I try to think about what I have as a reserve, or what toys I can bring into it. What I do is go blank, and the first images from my ‘grab bag’ that come into my mind show up, and I think, “well, I haven’t played with this one for awhile...” Everything is like a continuum of other processes that I’ve done before. At this age, I have this whole slew of reconnections to different points in time that I make.

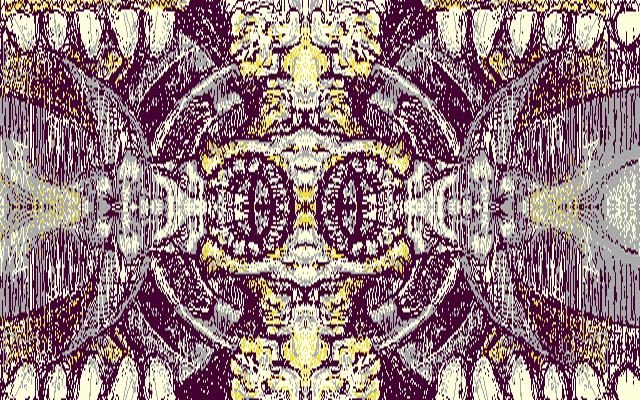

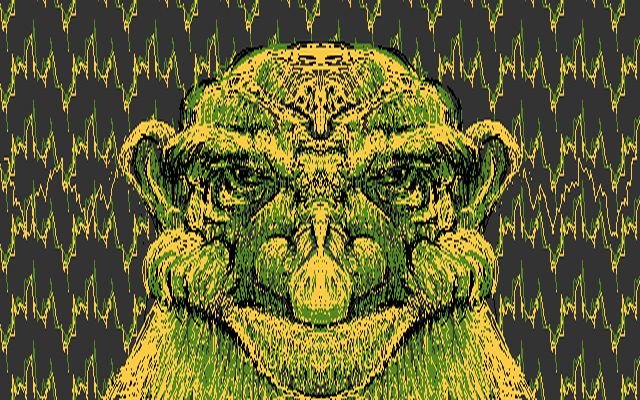

This was one of the first ones I had done, probably in the first year that I was playing with 3D computer animation. I was doing little demonstrations for students, and this was just proving that you can have two heads for the price of one. So that’s good — throw it in the back.

I always keep everything, which is terrible sometimes, because I can’t find anything, but a few years later I found it again. When I don’t know what I’m doing, I look back, so I pulled this thing out and refined it. Then it disappeared again. I had pulled it out a few weeks before, with a bunch of other imagery, because I’ve been crashing objects through each other. Most of those are essentially abstractions. I had thought, “what would happen if I slammed two bodies through?” And then this prompt came along, and I remembered this, from way back when. I don’t really think of things as finished works, as much as I think of things as the results of processes that I go through.

The other thing that’s important is that I always try to differentiate slightly that which I do completely on my own, from something that is a collaboration of some sort. I wouldn’t want to do something that was totally what I would have done anyway. One thing I did was to set a boundary to strictly stay on one thing for two weeks, which is rare for me these days. To just play off the variation of the variation. I’m retired- I can do that forever. At the beginning, I was trying to make these things work as faces going through each other, and then I started trying to go into a greater animation concept, and that seemed contradictory to me. I was moving it around, and making it jump, and it didn’t make sense with what the prompt was, or even what the head was. I decided to keep it in the middle position, so I didn’t wander all over the screen. I also decided to cut back on extreme variations of movement off of it.

I work with something called KeyShot, which is an animation program usually for products. I ended up getting it because of circumstances. I found that it’s really good, because there’s a bunch of sliders, and I can just sort of put a puppet together, and then I can say, “what would happen if I slide it over this way?”, or increase the speed, or something. And then I just sit back and watch it go for a while. And then when I found one that I liked, I just took a lot of pictures of it. It’s a really different process from making physical things out of materials, and I wouldn’t be able to do any of this computer stuff without the material knowledge behind me.

I think one of the things that I’ve been toying with on the computer recently, is what is the medium? As a studio endeavor, not as a production job. And I really love seeing Pixar, and all those- I’m totally fascinated by it, and wish I had that technology. One of those frames would make my computer render for half a year. But, what is the nature of it? I played this out with no gravity for awhile, and I’ve been doing this since I knew you- back in 2008. I started using a new software that allows me to create a head the same speed I could make it out of clay. I definitely don’t use the software the way the tutorials do. I never could follow directions, and the tutorials always discouraged me.

I first started working with computers in 1985. I liked them back then because they were so simple. I had a brick, and I had twelve colors, and if I wanted to make any more colors I had to make these giant pixel rug patterns. I really got into the pixels. The patterning, and the zigzags. After I did the Jumper in Boston [a bronze sculpture of a long jumper], I was able to use the funds to get my first computer. I became very aware of it as a material. I became fascinated with seeing my mark on a screen by just moving a mouse around. I found that I wasn’t as interested in what big industry was interested in, I was much more interested in kicking it around. Playing with it. I got into 3D modeling later, and it was the same thing. I realized that learning less was better in some ways then trying to learn everything about it.

One thing I remember you saying to me when I was your student, was to never forget about Murphy. I think about that all the time, and I wonder: how does that translate in this 3D space? Does Murphy’s law even exist?

Murphy’s law is completely there, because I can’t follow directions. I don’t understand half of this stuff. This is the difference between product and exploration: I simply am curious about certain aspects, and I want to make it into a studio process, so there are a lot of things that are accidents, and glitches, things that didn’t work. That’s why I started crashing objects together- I started differentiating between real and non-real. I sort of look at the stuff that we’re seeing now in the hi res end as like the Victorian age of painting. Just before there was a shift. The amazing accomplishments of making something that is completely believable, down to the sheen and layering. But it’s the same thing as everything else I see, in a different way. If you can do so much with reality, what can it do if it could fake out what’s not real, or what it is, as opposed to what it’s trying to be?

I’m totally frustrated half the time, because things don’t work out, but in the end I don’t really care if I get what I thought I wanted. I don’t feel that way in any of my artwork. So I try to set myself up to fail. That time when things aren’t working out is usually the time when you really start to become creative. There are two ways of reacting to failure. One is a total freak-out of unworthiness, and the other attitude is, “well, I’ve been here before. I’ve always gotten myself through it.” And pretty soon you get used to the uncertainty of it all. I wish I could take what I’ve learned in my studio back into the real world a bit more, and be more relaxed!

When you look at the piece you made, what does it say to you, on it’s own?

I just like looking at it.

Is it a meditation?

More likely that was an end-product of realizing what I had done. But I did think about not making it so much an animation, as a sculpture that moves. And that’s why I ruled out the gesturing and everything. I felt it was really best to keep it as simple as possible, and make it more of an experiential thing. Which is why I ended up with that light effect, which was going around with all those little lines and stuff. That made a counterbalance to a lot of the motions, and there were a lot of times when it accidentally matched, and then I would just mash it up a little bit. It was like setting up a bunch of actions, seeing what happened, and seeing what I could pull out and get away with. I think it’s more about what I can get away with. Because suddenly I get to a point where I can say, “that’s pretty cool.” I would say that the meaning is more of a result of a process, as opposed to some great thing I had to say about meditation. If anything, that’s more of a side issue for others to play with.

I recognize that I don’t make the work, as much as I make the skeleton for other people to fill with their own image making. I almost thought about putting music in, but I thought I would be cutting the bridge for someone. And if I started to make it too animated, that would be telling a story or forcing a person to think about it in a way that would be more restrictive. I always worry about what’s on page four, if I’m page three. I like to leave it open.

I actually don’t know what I’m making until it’s over, and then it’s done. I don’t think a lot of us know what we’re doing, until we’re doing it. That’s a hard thing to accept, but a game plan is only that which gets you to the door, to turn the handle. If you have an end product in mind, then you have a direction, and you know you can be a failure.

So true!

If you want to set yourself up for failure, you want to set yourself up positively for failure, so you have a wander. I read a good book about it once that talked about it this way: It’s like Wiley Coyote and Roadrunner- the coyote is too stupid to know he can’t get the bird, so he just keeps trying anyway. So, how this was set up: I knew there was going to be a game, I knew there was going to be something, and you dropped me some footprints. So I don’t even know what the identification is- I just look around and look for those footprints, and all the sudden I see a tail. And then suddenly I realize it’s a bull, and then all of the sudden, I have to beat the bull or he’s going to beat me. We have to have a discussion. And that comes from not knowing all the ways the recognition of what is, to the point where you now know what the process is even if you don’t know what the resolution is. And then all of the sudden, you have a mutual agreement about the way it is. And when you’re all done discovering the bull, and having an experience, then, according to this book, you’re supposed to go out and teach.

For myself, I feel like I’ve done an inversion. I’ve learned so much from the students, that I’m basically now doing what I taught. I had a long education- fifty years, it was finally time for me to graduate. I know how to teach myself, I’ve gone through seeing all the fear of the students, which I saw so much. That was painful at times- the fear of not being able to accomplish, or the fear of criticism. The way some faculty had criticism, like making people feel like they were absolutely worthless. It’s so horrible. I had to teach people how to have a critique. The idea is to try to find out what it is, and help the person with that, not necessarily say what it isn’t. Focusing on the intention of the project, versus the intention of the person. It’s a very subtle difference.

Can you say how that played out for you in this project?

It’s a subtle line. I know that whatever intention I had, it’s not going to be that. If I had said that I wanted something to be a certain way, or if I had to prove my self worth with it, that would be intentional. Whereas, what’s underneath a level of that, is more my felt feelings about what my intentions are. I’m sort of vagueing it out a bit here. But the intention of what I’m doing internally could be very different from saying “I want to make a head.” In that sense, I was basically just asking “how many heads can I get?” That was my curiosity. If someone said “I can’t read what those heads are,” then I would say back that I didn’t expect them to. If someone said that I had to do it that way, and I had to make each of those movements recognizable, and with exact timing, that would be a direction that would be a good thing to talk about, but may not be where I’m at.

Do you have any advice for someone else approaching this project for the first time?

I think the idea is not to try to illustrate the prompt. This is a reaction. I did a project in college once where we had to turn movement into words, I did that with drawing too in a way. The idea is to respond to how you react to it, that’s why the word is ‘prompt’. It’s not an assignment, it’s a prompt. You can read a prompt, and say, “I totally disagree and don’t like that,” and it would be valid. It’s not like you’re trying to match it. If you try to illustrate a poem with direct correlations, it’s not going to go anywhere because that’s not what the concept is. So, how the light moves around, and how that head moves in response to that, makes it something other than just matching.

What I think, is just don’t worry about it. Start with your first reactions. I don’t think one should worry about judgement in this case, because that’s definitely going to get in the way of trying to figure out what you’re doing, and when it’s done it’s done. I think the biggest problem is the concern with making a finished work. I think they should not worry about the finished work, and let the work happen. Have a conversation with their materials or ideas and the prompt, and rationalize it as it comes, rather than trying to solve it. It’s not a solution to solve, as much as an exercise to play.

A wander?

Yeah. It was a lot of fun. It’s not a matter of trying to make art, as much as a matter of visually trying to think about the experience of making art. And letting that process reveal thoughts that you haven’t had before. One of the things with my enthusiasm for what I’m doing now, is more about making stuff that I haven’t seen before as opposed to what I have seen. I want to make something that makes me want to make another one, as opposed to something that proves that I’m right.

I think the most important thing is not to get yourself taken away into what it should be. There are times when there’s something that you wish it would be, but that’s different from how it should be. All those things are preconceptions of what you thought, which is just what gets you to the door. A lot of times the preconceptions of what things are is what gets in the way of making things that you haven’t seen.

One other thing I want to throw out about the webbing around the thing, that was taken from another piece. Early on, with computers, I was trying to see how many heads you could make in a sphere. So that was one of those multi heads, and what I did as an experiment, was to distort the form a couple of times by bending and stretching a little, and ended up mapping, unintentionally, all these creases, which is where those lines are. Then I removed everything else, by just pressing a button, and then determining color stuff. But part of the fun for me was realizing that it was part of the assignment of different heads, and how many can you have? You can see the residue of teeth floating around and stuff, and you don’t really notice it. But if you keep watching it, you see it. And that’s why I thought about it as a meditation. If you watch it twice, you might notice something you hadn’t before, which is what I like seeing when I look at art. It’s a whole lot more interesting than making something that is, definitely, a goldfish.

Call Number: M35FI | M37FI.haLo

Specializing in sculpture, puppetry, and computer modeling, Thom Haxo is an imaginative artist who served as an associate art professor at Hampshire College for many years. His works have been exhibited several places, including the Holter Museum of Art, the Boston Public Library, and a commission for the James Brendan Connolly Memorial in Boston. Haxo has worked on set, puppet, and mask design for such projects as The Skriker by Caryl Churchill and I Stand Before You Naked by Joyce Carol Oates. Haxo received a B.F.A. from Pratt Institute and an M.F.A. from the University of Pennsylvania, and currently lives in Massachusetts.